First Car To Cross Australia

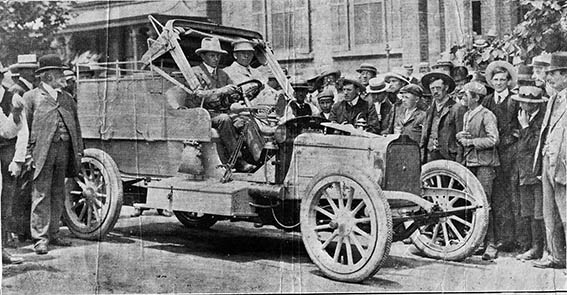

When a party of three weather-beaten men drove in to Darwin on August 20, 1908, in an equally weather-beaten British-made Talbot motor car, they became the first to drive a car across the Australian continent.

It was a feat that had taken two years, two tries and two cars, and only after 42 days and their second attempt did they manage to break down the tyranny of distance between Adelaide, the capital of South Australia, and Port Darwin, then the ‘capital’ of the Northern Territory of Australia.

At this stage of the motor car’s evolution, ‘motorists faced a hostile society of luddites, horse-loving reactionaries, regressive law makers and overzealous police’, Dr Kieran Tranter writes in his article ‘The History of the Haste-Wagons’.

There were only about 500 cars registered in South Australia; the car of the masses, the Ford Model T, was yet to be introduced to Australia; and the first west-east crossing by vehicle, by Francis Birtles.

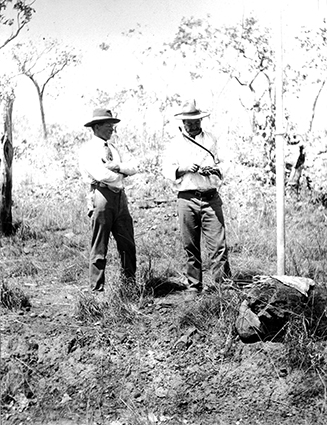

Harry Dutton, who owned the Talbot, was a 28-year-old heir to a pastoral fortune. He lived at his family home of Anlaby Station just outside Kapunda, north-east of Adelaide. In 1907 it was decided that he would attempt the first south-north crossing of the continent, a distance of about 3400km.

With him would be Murray Aunger, who Harry’s father had recommended as the companion for the trip. Murray had helped establish the Lewis Motor Works in SA in the late 1890s, and he built the first car in the state in 1900. The Lewis company was by 1907 a major supplier of cars to wealthy South Australians.

Murray was the brain and the muscle behind the crossing attempts, and Harry was to later say, “the trip’s success was attributable entirely to the ability of Mr Aunger”. Murray, a whizz at anything mechanical, also went on to hold a number of Australian motoring records.

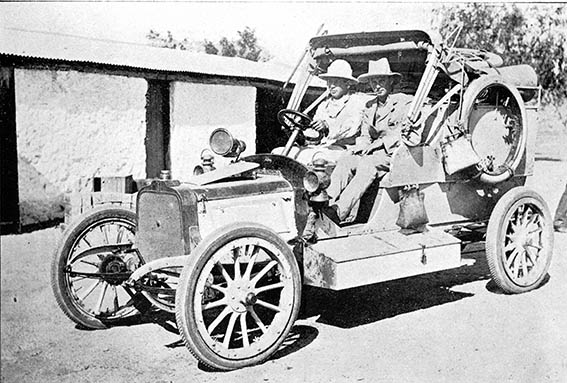

The first south-north attempt started in Adelaide on November 29, 1907, in a 15kW Talbot motor car they’d christened, ‘Angelina’.

The Talbot cars, built by Clement-Talbot Limited in London, quickly gained a reputation for being well-made, efficient and fast, and it was the first car, in 1913, to cover 100 miles (160km) in one hour. They were also expensive; a factory refurbished chassis was advertised at the time for £450, and a body for £350. That was more than most complete new cars when the average annual wage in Australia was just £158 per year!

A four-cylinder 3770cc water-cooled engine with mono-cast cylinders and a bore and stroke of 100mm x 120mm powered the vehicle. It had a rated output of 20hp (15kW). The 1908 model had its power increased to 25hp (19kW) and had a recommended cruising speed of around 75km/h.

These English cars often blew out, or dripped, more oil than they actually used, as they had no oil seals. Water use was also considerable, although the Talbots were equipped early on with a water pump, which made them more suited to Australian conditions than many other vehicle makes. The vehicles would also need greasing regularly, with a recommended greasing interval of just 900km.

The vehicle weighed around 1280kg and had a wooden body with a box featuring vertically opening doors in the rear. Its wheelbase was 9 feet and 8 inches long (2.95m) and its wheel track was 4 feet and 7 inches wide (1.4m).

The Talbot was fitted with wooden-spoke, artillery-type wheels originally running clincher-type tyres of about 35 inches by 5 inches (880mm x 120mm). Because tyre pressures of 60psi tyre were standard, they were highly susceptible to blowouts and coming off the rim.

Dutton or Auger never mentioned that, and they reported having only three punctures for the whole of the second trip. They probably ran lower tyre pressures because of the rough, mainly sandy terrain (and slow going), or maybe they used Michelin all-terrain-type tyres with a steel stud tread pattern; that’s a tyre brand that is still known for its great off-road rubber, although the steel studs have gone.

The front wheels were on a standard axle on semi-elliptical springs. The live rear axle was on half-elliptic springs and a transverse spring, giving the rear suspension a great degree of flexibility to cross rough terrain; there were no shock absorbers.

The gearbox was a three-speed unit and included a reverse gear, while the diff was of a conventional bevelled gear drive with fully floating hubs. The footbrake operated on the transmission, while the handbrake operated a contracting band on the rear wheels. There were no front brakes!

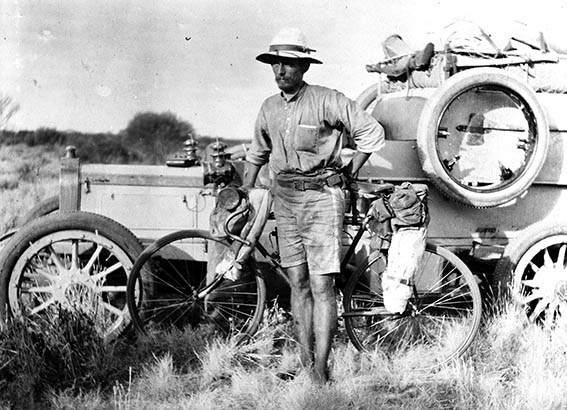

The vehicle was equipped with kerosene lamp lights, a speedometer and a gradiometer. Attached to the sides were a shovel, pick and an axe, while a rifle and a block and tackle made it into the survival/recovery kit. A complete set of spare tyres and a vulcanising kit for repairing both covers and tubes were also carried, along with assorted spare parts.

Provisions for a week found a spot in the heavily loaded vehicle, which had been modified to carry 385 litres of petrol. All up the vehicle weighed more than two tonnes.

Extra supplies of petrol and oil were sent ahead to Oodnadatta (the rail head for the Ghan Railway at the time), Alice Springs, Katherine (then called Catherine Creek), and Pine Creek, the latter just 225km south of Darwin.

The week before they set out, the car was tested in the sand hills of Henley Beach. The Kapunda Herald newspaper reported, “... with grades of one in seven, and though the wheels sank to the axles, the car ploughed through the sand without difficulty. The car is cream colored [sic], and not ungainly in appearance.”

Once the expedition set off, for the first couple of hundred kilometres after leaving Adelaide, the roads were good and the progress was excellent. But once they left the small town of Hawker, in the heart of the Flinders Ranges, the route followed the Overland Telegraph Line (OTL) and the horse track that ran beside it.

As they skirted around Lake Eyre, numerous dry and sandy creeks were crossed and, as the Brisbane Telegraph reported, “because of the steepness of their banks and the sandy character of their beds, in which the car wheels spun around uselessly, the motorists were obliged to construct corduroys in order to enable the car to negotiate these crossings.”

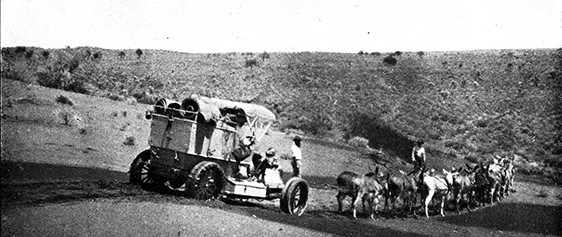

But even tougher going was ahead. When they reached Alice Springs on December 16, Harry Dutton wired from the Telegraph Station, and the Melbourne Table Talk weekly magazine reported later that month, “...that he is perfectly satisfied that the notorious Depot Sandhills, which extend for twenty five miles between Horseshoe Bend and Alice Well, and of which overlanding cyclists have always given such a lurid report, are too much for any car without outside assistance.”

The report from Harry Dutton continued: “The country was practically a billowy sea of soft sand. When the 20hp Talbot was set at the stiff inclines the loose drift-sand offered no resistance to the tyres, which simply spun round at terrific speed and tore great gaping holes into the ground.

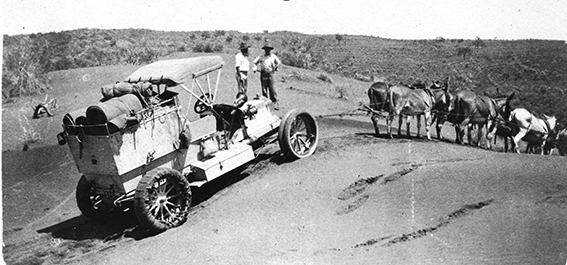

Block and tackle were tried without success and even when the car had the assistance of a team of donkeys to haul it over the stiffest pinches there was considerable difficulty in steering the car, for the front wheels sank so deeply into the soft sand that it banked up in front of the front axle and had to be shovelled away.

With a temperature of 114 (45°C) in the shade, it can easily be imagined what Messrs. Dutton and Aunger went through out on the barren sandhills. So far they have experienced no trouble with the car, which is standing the rough use splendidly.”

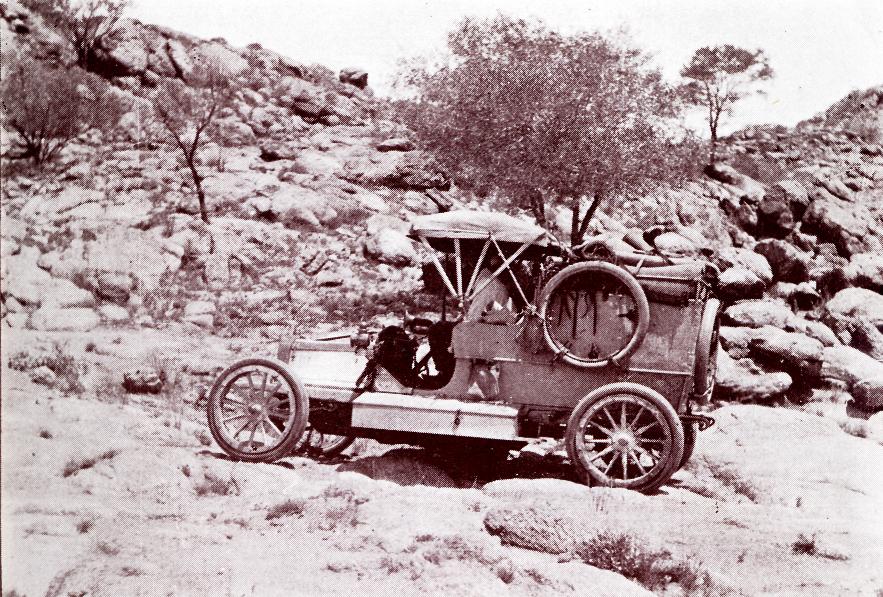

The two men and the tough Talbot pushed on through the rocky barrier of the MacDonnell Rangesand out on to the plains where they were plagued by tall grass and hidden termite mounds that could have smashed their steering, suspension or diff. Here, in this remote country, Dutton and Aunger met Francis Birtles, who was heading south on one of his many cycling record attempts across and around Australia.

But the team’s luck ran out soon afterwards. South of the Tennant Creek Telegraph Station (there was no town at this time), the pinion in the Talbot’s diff collapsed and, with the onset of the Wet Season, the vehicle was abandoned. Dutton and Aunger returned south to Oodnadatta on horseback and transferred to a train to travel on to Adelaide.

Undeterred by their failure, Harry bought another Talbot, this one a more powerful 25hp version, known as the Overlander (or ‘474’ – its rego number). Once again it was modified for the trip, much the same as Angelina had been, and on June 30, 1908, the two men once again set out from Adelaide.

They reached Hergott Springs (now Marree) on July 4, and then Oodnadatta after another week’s hard work in the sandy creeks around Lake Eyre. The report written in the Brisbane Telegraph in September 1908 captures some of the harshness of the trip through the sandy country farther north: “Progress through this class of country necessarily was slow, an average of 40 or 50 miles a day being as much as could be maintained ... one occasion a full day’s hard work only reduced the distance to Port Darwin by 10 miles ...”

At Alice Springs, the telegraph station officer, Ern Allchurch, joined the two men for the rest of the journey, and 30 days out from Adelaide, after a tough time in among the rocks and narrow passes of the MacDonnell Ranges, they came across the abandoned Talbot, Angelina.

She was in a pretty good state, considering the lengthy time spent out in the elements.

Some of the car’s woodwork had shrunk, the two rear tyres had perished, the locks were broken and some equipment had gone missing, and there was a healthy collection of spiders, wasps and centipedes to clean out. But it wasn’t long before the older vehicle was repaired and mobile once more with Harry at the wheel, while Murray drove the newer car.

.jpg)

They reached the Tennant Creek OTL station soon afterwards and pushed on. On August 8, as the party approached Daly Waters, they were caught in a vicious scrub fire. They were forced to make a 10-mile (16km) run through the inferno, puncturing three tyres on the fire-blackened stumps; the only punctures suffered on the trip!

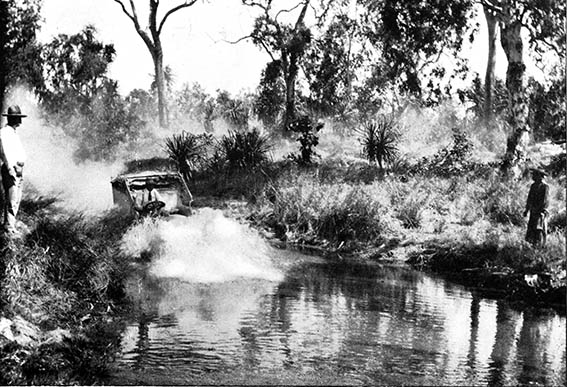

Luckily, they made it safely through and a few days later reached the Katherine River, which surprisingly offered no great resistance to the group. The Edith Creek, though, a little further north, by Dutton’s report to the Brisbane Telegraph, “... proved a much more formidable obstacle. Here it was found necessary to cover the engines and rush the cars through the stream at top speed.”

Pine Creek, at the southern end of the then-railway line from Darwin, and 69 miles (111km) north of Edith Creek, was reached after a mammoth one-day run. From there, the men expected a relatively easy drive north but, with the coming of the railway line, the road to Darwin had been almost abandoned; its many bridges had been destroyed and the road had been washed away.

Angelina was already struggling in the creek crossings and was sent ahead on the train (the extra 3.5kW that the Overlander sported obviously made a massive difference).

The party pushed on in the Overlander and at Union Town (now abandoned), not far from Pine Creek, the locals confidently predicted that the expedition would end in failure or disaster. With those dire words hanging in the men’s ears, they drove on and, at Bridge Creek, a short distance farther north, found themselves looking at a sheer-sided creek, about nine metres deep and with a sharp turn at the bottom.

Now, the reporter with the Brisbane Telegraph must have been excited, because I’m pretty sure, staid old Harry wouldn’t have written this in his telegram: “It was a case of ‘do or die’.

Reversing the engines, therefore, and pulling the brakes hard down, they launched the cars over the bank of the creek, and, after a looping-the-loop experience with a serpentine instead of a somersault turn at the bottom of the creek, each found himself rushing at the opposite bank, the steel-shod tyres striking showers of sparks from the boulders as they struck against them. Pluck and perseverance again were victorious ...”

As they got closer to their final destination, the jungle and verdant scrub closed in around them and they reported being covered in ants, spiders, “and other pestiferous denizens”. The party drove in to Port Darwin on the evening of the August 20, 1908, to “public rejoicing” and later a function was held in their honour.

While the men hadn’t explored any new country or blazed a new trail across the continent, what they had achieved was hailed as a great achievement right across the continent and proved that the motor vehicle was a force to be reckoned with.

The motor car, though, would take another 20 or 30 years to supplant the horse and camel, but in the meantime other adventurous souls read about Dutton and Aunger’s trip and set out on their own incredible travels.

100 years on, we take our cue from such great Australian travellers as Len Beadell and the Leyland Brothers, but we all follow in Dutton’s and Aunger’s footsteps when we travel the Oodnadatta Track, the old Ghan Line and the Stuart Highway north of Alice to Darwin. Tip your hat to them on the next trip north!

The Talbots and National Motor Museum (NMM)

Angelina was sold and destroyed by a fire in 1915, although its box body is the one you see on Overlander today at the NMM.

The Overlander was used for many years on the Dutton’s property, and, in 1959, Harry’s sons re-enacted the trip and drove the vehicle once again from Adelaide to Darwin. There was a road by then, but it was a bloody rough one – nothing like today’s Oodnadatta Track or Stuart Highway.

In 1977 the Birdwood Mill Museum purchased the vehicle, which was in pretty good condition, having been restored for the ’59 trip. It was refurbished again for the 1988 Castrol Bicentennial World Rally. Then in 2008 the Talbot followed – but didn’t drive – the original route as the travelling exhibition, Off the Beaten Track.

The vehicle is still in working condition and has pride of place at the National Motor Museum in Birdwood, South Australia.

While it is worthwhile to go to the museum for this vehicle alone, there are many other standouts housed and on display there. These include Tom ‘the Birdsville mailman’ Kruse’s truck; the Leyland Brothers’ Land Rover, which was the first to cross the continent from Steep Point to Bryon Bay; and many other truck and motoring classics.

Article reproduce by kind permission of Ron & Viv Moon

THE TALBOT OWNERS CLUB MAGAZINE

The Talbot Owners Club magazine is published bi-monthly and contains news, updates and informative articles. It is edited by club secretary David Roxburgh.

GO TO DOWNLOADS

TALBOT OWNERS CLUB MEMBERSHIP

The essence of the Club is to ensure that members meet and enjoy themselves; the Club is open and democratic, dialogie is encouraged. It is for people of all ages who like Talbot cars and want to enjoy the company of like-minded people and also to support current Talbot involvement in historic competition.